Wetlands

Wetlands are among the world’s most

important and hardest-working ecosystems, rivaling rainforests

and coral reefs in productivity.

Wetlands are among the world’s most

important and hardest-working ecosystems, rivaling rainforests

and coral reefs in productivity.

They produce high oxygen levels, filter water pollutants, sequester carbon, reduce flooding and erosion and recharge groundwater.

Half of all animals and a third of all plants on California’s endangered species list live in wetlands. Wetlands also draw bird watchers and hunters and photographers.

Californians drained and developed most of the state’s marshes, swamps and tidal flats, losing as much as 90 percent of the original wetlands — more than any other state. While the conversion of wetlands has slowed, the loss in California is significant and affects a range of factors from water quality to quality of life.

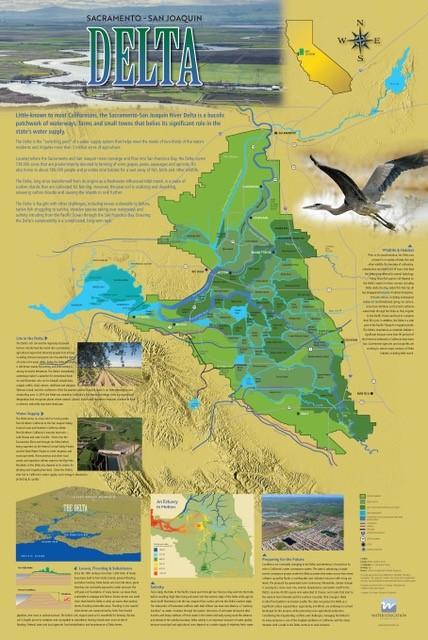

Wetlands remain in every part of the state, with the greatest concentration in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and its watershed, which includes the Central Valley. Wetlands in the Delta’s watershed take on special significance because they are part of the vast complex of waterways that provide two-thirds of California’s drinking water.

Overview

Wetlands include bogs, swamps, estuaries and marshes connected to streams, groundwater, rivers, lakes and coastlines. Most of California’s wetlands are semi-aquatic links in a water-based chain extending from the Sierra Nevada mountain range to the Pacific Ocean.

Wetlands can be permanent or seasonal. Tidal wetlands are flooded or drained twice daily. Seasonal wetlands include tule fields and vernal pools and share many of the same types of soils, plants and animals as permanent wetlands.

One acre of wetlands can filter 7.3 million gallons of water a year. You can see an example of a wetland in this video of the San Luis National Wildlife Refuge in the San Joaquin Valley.

California’s wetlands are predominantly freshwater including riparian wetlands along lakes and rivers. Tens of millions of migratory birds depend on riparian and wetland habitats in the Central Valley and Colorado River Delta, a 2021 National Audubon Society study found,

Benefits

Wetlands soil and vegetation act as kidneys for watersheds, filtering water and absorbing nutrients and contaminants. Other benefits of wetlands include:

- Flood control

- Groundwater recharge

- Habitat for fish, waterfowl and other wildlife

- Erosion control

- Shoreline protection

- Seawater intrusion mitigation

- Carbon sink to mitigate climate change

Looking Ahead

Science has shown that California’s

wetlands are part of a large, interconnected system and can be a

tool in helping the state meet its carbon reduction mandate. To

protect one element in it, all must be addressed. While

protecting wetlands is a continuing emphasis, so is the

acquisition and restoration of wetlands.

Science has shown that California’s

wetlands are part of a large, interconnected system and can be a

tool in helping the state meet its carbon reduction mandate. To

protect one element in it, all must be addressed. While

protecting wetlands is a continuing emphasis, so is the

acquisition and restoration of wetlands.

California and the federal government have been at odds over how widely to define wetlands protections. The federal government and the U.S. Supreme Court have tended to narrow the definition of waters of the United States that are subject to the Clean Water Act.

In response, the State Water Resources Control Board sought to protect California’s non-navigable wetlands under the state’s Porter-Cologne Water Quality Control Act. However, a 2021 Sacramento Superior Court ruling found that the state is not authorized to take such an action for wetlands that do not meet the federal definition of waters of the United States.