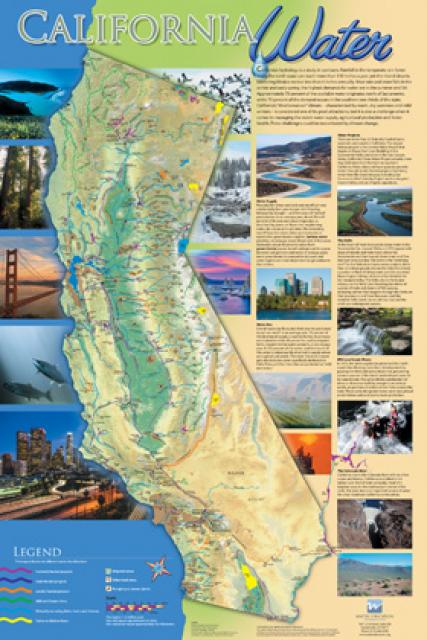

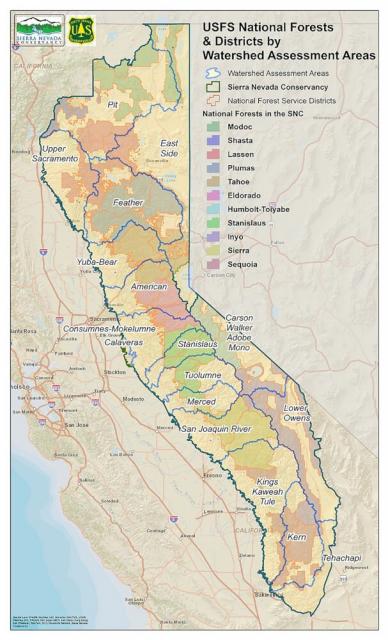

Sierra Nevada

Stretching 450 miles long and up to

50 miles wide, the Sierra Nevada makes up more than a quarter of

California’s land area and forms its largest watersheds,

providing more than half of the state’s developed water supply to

residents, agriculture and other businesses.*

Stretching 450 miles long and up to

50 miles wide, the Sierra Nevada makes up more than a quarter of

California’s land area and forms its largest watersheds,

providing more than half of the state’s developed water supply to

residents, agriculture and other businesses.*

The Sierra is also one of the world’s most diverse watersheds, with granite cliffs, giant sequoias and lush meadows on the western slope, and stark desert landscapes at the base of the much steeper eastern side. Its habitats support two-thirds of the state’s bird and mammal species, including bighorn sheep, mule deer, black bear, mountain lions, hawks, eagles and native trout.

Rain and snowmelt running off the range goes to irrigate farms that produce half of the nation’s fruits, nuts and vegetables, and accounts in part for California becoming the nation’s largest dairy producer.

The mountain runoff supplies at least part of the drinking water for some 30 million Californians.

Many Sierra rivers are dammed to store and release this runoff when needed. Hetch Hetchy Reservoir in Yosemite National Park, for example, supplies 2.7 million residents and thousands of businesses in four Bay Area counties. Reservoirs fed by the Mokelumne River supply more than 90 percent of the East Bay’s water and Eastern Sierra runoff in the arid Owens Valley is a major supply for Los Angeles.

Snowpack & Runoff

The Sierra watershed provides much of California’s water because the mountains topping at 14,505 feet above sea level on Mount Whitney catch eastern-moving clouds fattened by the Pacific Ocean.

The snowpack that accumulates in the

winter acts as a natural reservoir that holds water until

temperatures rise in spring. The snowmelt captured in upper

elevation creeks and streams replenishes Sierra rivers and

reservoirs and recharges groundwater basins in the Central

Valley.

The snowpack that accumulates in the

winter acts as a natural reservoir that holds water until

temperatures rise in spring. The snowmelt captured in upper

elevation creeks and streams replenishes Sierra rivers and

reservoirs and recharges groundwater basins in the Central

Valley.

Dam operators allow more of the spring runoff to fill reservoirs as flood risks subside. By late summer, when natural river flows are low, releases from the reservoirs supply much of the downstream water supply.

Most of the runoff ends up in California’s two longest rivers, the Sacramento (447 miles) and the San Joaquin (330 miles), which join just south of Sacramento and mingle with tributaries and Pacific tidal flows to form the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

Much of the Sierra water that historically flowed into the Delta is now diverted by upstream users and Delta farmers and exported through the State Water Project and the federal Central Valley Project. The giant delivery systems supply cities and farms in the south Bay Area and throughout Central and Southern California.

Watershed Challenges

The Sierra Nevada faces several environmental pressures, including:

- California’s growing population and the increased water demand, pollution and development that come with it

- More frequent and more destructive forest fires – a fallout of climate change – and the resulting erosion that reduces reservoir capacity and muddies drinking water supplies

- Tree mortality caused by drought and related beetle infestations which, like forest fires, are worsening with climate change

- Gold mining’s ongoing legacy of mercury contamination and excessive sediment in Sierra streams and rivers

Climate Change

The effects of climate change in the Sierra are also seen in the declining snowpack and earlier snowmelt. In the past 100 years, annual runoff from April to July has decreased by 23 percent in the Sacramento basin and 19 percent in the San Joaquin basin, according to state climate statistics.

Many groups and agencies at the local, regional, state and federal levels are working to restore upper watershed forests and meadows, reduce the risk of large wildfires and better protect the quality and reliability of water supplies. Significant state funds from bond measures have been invested in the Sierra watershed by the Sierra Nevada Conservancy, California Department of Water Resources, and the California Wildlife Conservation Board.

*On average, more than 60 percent of California’s developed water supply originates in the Sierra and, to a small extent, the Cascade Range in northeastern California, according to California’s Water Resilience Portfolio of 2020.