Questions Simmer About Lake Powell’s Future As Drought, Climate Change Point To A Drier Colorado River Basin

WESTERN WATER IN-DEPTH: A key reservoir for Colorado River storage program, Powell faces demands from stakeholders in Upper and Lower Basins with different water needs as runoff is forecast to decline

Sprawled across a desert expanse

along the Utah-Arizona border, Lake Powell’s nearly 100-foot high

bathtub ring etched on its sandstone walls belie the challenges

of a major Colorado River reservoir at less than half-full. How

those challenges play out as demand grows for the river’s water

amid a changing climate is fueling simmering questions about

Powell’s future.

Sprawled across a desert expanse

along the Utah-Arizona border, Lake Powell’s nearly 100-foot high

bathtub ring etched on its sandstone walls belie the challenges

of a major Colorado River reservoir at less than half-full. How

those challenges play out as demand grows for the river’s water

amid a changing climate is fueling simmering questions about

Powell’s future.

The reservoir, a central piece of the storage program for the Colorado River, provides water, hydropower and recreation to millions of people. It was designed to ensure that Wyoming, Colorado, Utah and New Mexico can meet their legal obligation to let enough water pass to Arizona, California and Nevada, as well as supplying water to Mexico.

But persistent drought in the Colorado River Basin over the last 20 years and the need to keep Lake Mead, Powell’s twin reservoir downstream, from reaching critically low levels have left Lake Powell consistently about half-full. Some environmental advocacy groups, aiming to restore Glen Canyon, have called for the dam’s decommissioning.

Water managers say that’s unlikely, given Lake Powell’s key role in meeting downstream obligations and the interest of some upstream who hope to tap its waters. Recent studies point to warmer and drier conditions ahead, with reduced runoff into the river. A rewrite of the river’s operating guidelines is on the horizon, and already there is talk about how those guidelines could affect Powell.

Lake Powell and Lake Mead currently adhere to an operations protocol that determines release volumes from Lake Powell to Lake Mead and how Lower Basin water users enjoy the benefits of surplus conditions or the shared sacrifice of delivery cuts during shortage. The rules for these scenarios are found in the 2007 Interim Guidelines, the 2019 Drought Contingency Plans and international agreements with Mexico.

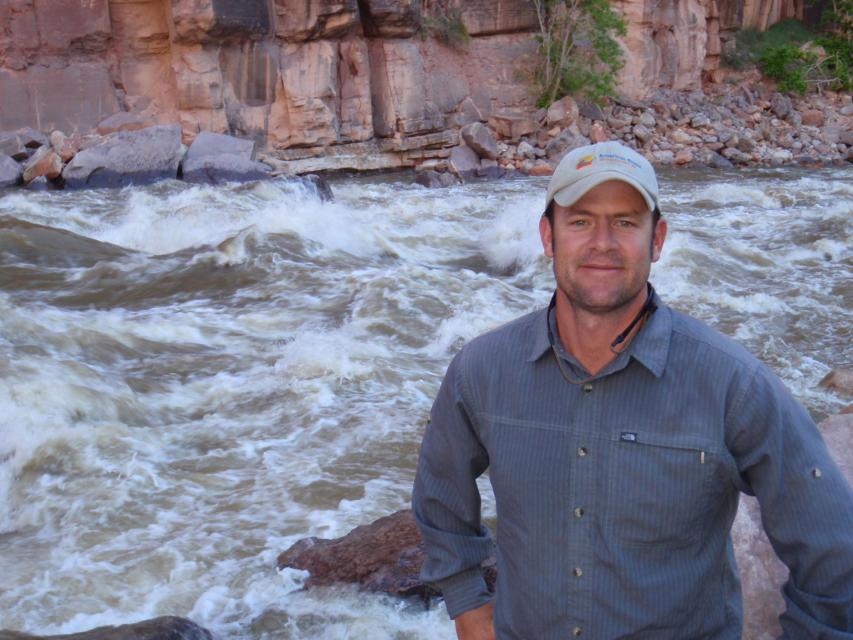

“I think an honest and thorough look into the future of Lake Powell is absolutely warranted.”

~Matt Rice, director of American Rivers Colorado Basin Program

Chief among the Guidelines’ provisions is better coordination of the operations of Lake Powell and Lake Mead each year.

As key stakeholders prepare to forge the next set of management guidelines that will update those from 2007, there may be a reassessment of Lake Powell’s operations so that it can take on the coming challenges.

“I think an honest and thorough look into the future of Lake Powell is absolutely warranted,” said Matt Rice, director of American Rivers Colorado Basin Program.

Rice, part of a February forum on the future of Lake Powell, said the crisis wrought by the coronavirus pandemic shows how rare “black swan” events can emerge and shatter existing management plans, such as those for watersheds.

The dry conditions have prompted Colorado River water agencies to undertake unprecedented, collaborative efforts to ensure water supplies are not disrupted. In Las Vegas, for instance, rebates to homeowners by the Southern Nevada Water Authority have converted 193 million square feet of thirsty grass lawns into water-efficient landscaping.

Staying ahead of future crises is critical, and officials are informally discussing the parameters of the next set of guidelines. How those talks affect future water levels at Lake Powell and Lake Mead will be significant.

A Reliable Lake Powell

Conditions on the river are never static. In some years, a large snowpack produces voluminous runoff, but the science is showing a pattern of decreased flow from tributaries into the mainstem Colorado River. Earlier this month, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Colorado Basin River Forecast Center projected inflow to Lake Powell from April to July would be 65 percent of average.

Upper Basin users, meanwhile, want

to access their share of Colorado River water to meet growing

demands. In Utah, a 140-mile pipeline proposal would divert as

much as 86,000 acre-feet annually from Lake Powell to growing

communities in the state’s southwest corner. Utah officials

believe the $1 billion plan is necessary for places such as St.

George that are bumping against their limits of water supply.

Upper Basin users, meanwhile, want

to access their share of Colorado River water to meet growing

demands. In Utah, a 140-mile pipeline proposal would divert as

much as 86,000 acre-feet annually from Lake Powell to growing

communities in the state’s southwest corner. Utah officials

believe the $1 billion plan is necessary for places such as St.

George that are bumping against their limits of water supply.

Furthermore, Utah officials say the state is well within its right to access water it has rights to.

“Utah’s right to develop water for the Lake Powell Pipeline is equal to, not inferior to, the rights of all the other 1922 [Colorado River] Compact signatory states,” Eric Millis, then-director of the Utah Division of Water Resources, said in a 2019 statement by the state’s Department of Natural Resources. The Colorado River Compact divided the Basin into an upper and lower half, with each having the right to develop and use 7.5 million acre-feet of river water annually.

Meanwhile, the Navajo Nation is also looking at tapping Lake Powell water via pipeline so it can supplement limited groundwater supplies.

“The continued existence of Glen Canyon Dam is imperative if the Navajo Nation is to obtain a reliable supply of water from the Colorado River,” said Stanley Pollack, an attorney for the tribe. “A water line only works if you have Lake Powell.”

“The continued existence of Glen Canyon Dam is imperative if the Navajo Nation is to obtain a reliable supply of water from the Colorado River.”

~Stanley Pollack, an attorney for the Navajo Nation

In the Upper Basin, there is concern that Lake Powell has been increasingly called on to help Lake Mead, with not much to show for it.

“We are not improving the health of Lake Mead and … until and unless the Lower Basin addresses its overuse … Mead is not going to improve and it’s just going to bring the elevations of Powell down,” said Amy Haas, executive director of the Upper Colorado River Commission.

The storage/release paradigm between the two reservoirs has caused the most tension since adoption of the 2007 Interim Guidelines, said Colby Pellegrino, director of water resources for the Southern Nevada Water Authority.

The Upper Basin recognizes its obligation to let enough river flow pass to the Lower Basin, but occasional machinations with Lake Mead’s storage can be touchy. “Sometimes water is moved from Lake Mead downstream to other reservoirs or water users in a different pattern or timing, prompting concern from people in the Upper Basin that its neighbors seek to game the system,” she said.

The largest reservoir in the United States, Lake Mead receives the lion’s share of attention because of the efforts to keep it viable and supplying water to the many farms and urban areas – Las Vegas, Los Angeles and Phoenix, among them – south of Hoover Dam. In 2015, a third, deeper intake was completed at the lake to keep water flowing to Las Vegas’ 2 million residents and 40 million annual visitors. The lake supplies about 25 percent of the water needs of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California – even more during drought.

Having a reliable Lake Powell to back up Lake Mead is crucial especially during a period of uncertainty, Lower Basin users say.

“As we get into flashier, more volatile hydrology cycles with climate change we can likely see the occasional huge storm years with less snow and more rain,” said Jeff Kightlinger, general manager of Metropolitan Water District, the largest supplier of treated water in the United States. “Having readily available storage capacity for the occasional mega year will be extremely valuable.”

‘The Most Wonderful Lake in the World’

Controversial from the start, Lake Powell remains polarizing to some degree. Former Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Floyd Dominy, who spearheaded construction of Glen Canyon Dam that created Lake Powell in the early 1960s, said in a 2000 interview that Powell is “the most wonderful lake in the world [and] my crowning jewel.”

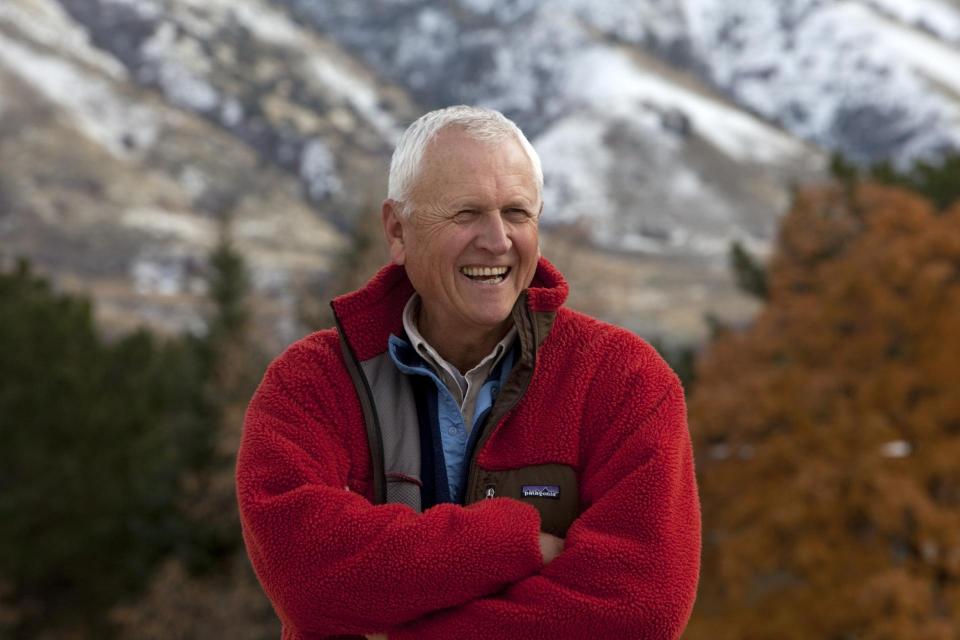

Former Reclamation Commissioner Dan

Beard, who served in the 1990s during the Clinton administration,

opposes the continued existence of Glen Canyon Dam. Because

climate change and further reductions in runoff will cause Lake

Powell to keep dropping, he said, stakeholders should focus their

energy on saving Lake Mead.

Former Reclamation Commissioner Dan

Beard, who served in the 1990s during the Clinton administration,

opposes the continued existence of Glen Canyon Dam. Because

climate change and further reductions in runoff will cause Lake

Powell to keep dropping, he said, stakeholders should focus their

energy on saving Lake Mead.

“Lake Mead is the heartbeat of the Colorado River,” Beard said. “It is a vital and important part of the delivery system for water to the Lower Basin states and to Mexico. It is a critical facility and yet it continues to decline.”

Beard is a board member with the advocacy group Save the Colorado, which, along with the Center for Biological Diversity and Living Rivers last year sued the federal government to force examination of climate change science in the management of Glen Canyon Dam.

The litigants say Reclamation and the Department of the Interior should conduct a revised analysis and include a full range of alternatives based on predicted climate change-related impacts on the flow of water in the Colorado River.

“Such a full range must include an alternative that incorporates the decommissioning and removal of Glen Canyon Dam because the projections from the best available climate science indicate there likely will not be sufficient flow in the Colorado River to keep Lake Powell and Glen Canyon Dam operational,” a press release accompanying the lawsuit said.

At capacity, Lake Powell holds more than 26 million acre-feet of water that originates as snowpack from the Upper Basin states of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico. That water gets released to Lake Mead via the Grand Canyon and helps supply the Lower Basin — Arizona, Nevada, California – as well as Mexico.

However, since 2002 Lake Powell’s water elevation has rarely gone above its historical 50-year annual average of 3,639 feet above sea level, the point at which it contains about 15.8 million acre-feet of water. The operating system is flawed, some experts say.

Two years ago, the Colorado River Research Group, a highly respected group of Colorado River scholars including Colorado State University’s Brad Udall and University of Arizona’s Karl Flessa, produced a publication called It’s Hard to Fill a Bathtub When the Drain Is Wide Open: The Case of Lake Powell. In it, they noted that the system is stacked against Lake Powell in part because of an overallocated Colorado River system.

Lake Powell and Lake Mead operate under multiple laws and agreements that are collectively known as the Law of the River. Under the rules, Lake Powell is obligated to release a certain amount of water each year to Lake Mead for the Lower Basin states.

The Lower Basin states, however, collectively draw about 1.2 million acre-feet more water from Lake Mead than Lake Powell releases in a normal year. The result is a so-called “structural deficit.”

“The structural deficit is the true

villain in this story, mixing with the operational rules to drain

Lake Powell,” the Colorado River Research Group publication said.

“If storage in Lake Powell cannot rebound in an era where the

Upper Basin consumes less than two‐thirds of its legal

apportionment, then the crisis is already real.”

“The structural deficit is the true

villain in this story, mixing with the operational rules to drain

Lake Powell,” the Colorado River Research Group publication said.

“If storage in Lake Powell cannot rebound in an era where the

Upper Basin consumes less than two‐thirds of its legal

apportionment, then the crisis is already real.”

Answers, the authors say, lie partly in the ability of Lake Powell storage to recover in wet years, reducing use in the Upper Basin and re-thinking exiting reservoir management. “Lakes Mead and Powell, after all, are essentially one giant reservoir and … thinking of these facilities as two distinct reservoirs, one for the benefit of the Upper Basin and one for the Lower, now seems outdated,” the publication said.

Haas, with the Upper Colorado River Commission, said the existing operating guidelines leave room for improvement. “I feel very strongly that as long as our reservoir operations are coordinated … the future of Lake Powell hinges on the future of Lake Mead,” she said. “We need to find a more equitable mechanism by which reservoir operations are coordinated.”

Marlon Duke, spokesman with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency that manages the river, acknowledged that Lake Powell draws scrutiny.

“I often get asked, ‘What’s the deal with Lake Powell?’” he said. “Shouldn’t we just drain it or is it really doing what it is supposed to do?”

The answer, Duke said, means looking

at the lake’s performance and how it has met expectations during

difficult times. Powell was near capacity in 2000. Then a period

of record-setting dryness set in. Through it all, enough water

was released to meet the Upper Basin’s obligation to the Lower

Basin.

The answer, Duke said, means looking

at the lake’s performance and how it has met expectations during

difficult times. Powell was near capacity in 2000. Then a period

of record-setting dryness set in. Through it all, enough water

was released to meet the Upper Basin’s obligation to the Lower

Basin.

People in the respective basins view Lake Powell and Lake Mead with a certain degree of ownership, and perspectives vary. Upper Basin interests generally want a more robust Lake Powell. South of the lake, the desire to tap into it further is not uncommon in the Lower Basin. The degree of change, ultimately, will likely fall between those sentiments.

All of that notwithstanding, it’s important to understand the two reservoirs are tightly woven, said Jack Schmidt, the Janet Quinney Lawson chair of Colorado River studies at Utah State University.

“It’s one big system and whether Powell [or Mead] goes up or down …those are intentional societal decisions of management that have little to do with climate change,” he said.

Schmidt co-authored a 2020 white paper, Managing the Colorado River for an Uncertain Future, which cautions that future flows will be “lower, more variable and more uncertain.”

“Powell, even less full going forward, remains a valuable piece of very expensive infrastructure that will remain part of the Colorado River storage pool for decades to come.”

~Jeff Kightlinger, general manager of Metropolitan Water District

Schmidt in 2016 analyzed the concept of “Fill Mead First,” the idea of establishing Lake Mead as the primary water storage facility on the mainstem river and relegating Lake Powell to a secondary storage role when Mead is full. The savings in evaporation and seepage losses would be relatively small, Schmidt said, but the idea shouldn’t be completely discounted.

Fill Mead First “generates passions and emotions,” Schmidt said. It is embraced by some as a restorative opportunity for Glen Canyon. “Then there is the world of traditional water managers who say that’s a ludicrous idea and we don’t pay any attention.”

The disparate views “live in two worlds completely.”

But Kightlinger, with Metropolitan Water District, discounts the idea of draining Powell. “Politically, I don’t see any real support or push for a fill Mead first strategy,” he said. “Powell, even less full going forward, remains a valuable piece of very expensive infrastructure that will remain part of the Colorado River storage pool for decades to come.”

A Warmer and Drier Basin

A small army of water professionals and experts constantly analyze the Colorado River Basin, which supplies water to 40 million people and fuels a huge agricultural economy.

For years, scientists have looked at the drying conditions of the Colorado River Basin, employing techniques such as tree ring sampling. Analysis of that method has shown that the years 1905 to 1922 – just as the river’s waters were being allocated among the states — were exceptionally wet.

In 2012, Reclamation’s Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study confirmed there are likely to be significant shortfalls in coming decades between projected water supplies and demands in the Colorado River Basin. Since the study, a steady stream of research points to warmer and drier conditions.

In April, a study published in the journal Science said the current dry period in the Southwest is one for the record books, and that its “megadrought-like trajectory” is fueled by natural variability superimposed on human-caused warming. Also in April, experts with the Western Water Assessment, whose researchers work out of the University of Colorado, Boulder and several other institutions in the region, noted that the severity and length of drought conditions can be difficult to quantify.

“This is especially true for the Colorado River system, in which total consumptive use plus other depletions typically exceeds supply, such that under even average hydrologic conditions the levels of Lake Mead and Lake Powell will tend to decline,” according to Colorado River Basin Climate and Hydrology: State of the Science, the study conducted by the Western Water Assessment.

The continued variability justifies a robust Lake Powell, said Haas, with the Upper Colorado River Commission.

“We know that future flows are going to be more variable and almost clearly lower, but we also need to ensure that our non-depletion obligation is satisfied,” she said. “Powell is our repository for this water. Doing away with the reservoir, in light of our 1922 Compact obligation, is not realistic,” she said.

Furthermore, an improved, more accurate forecasting approach is needed ahead of the next set of operating criteria. “That’s especially true given the vicissitudes of hydrology and the impacts of climate change,” Haas said.

Increasing Lake Powell’s releases is potentially problematic because of the likelihood that predator fish from Lake Mead could make it upstream and devastate native fish in the Grand Canyon.

As it stands, Pearce Ferry Rapid, a rugged, impassable cataract located near the downstream end of the Grand Canyon, prevents predators such as catfish, bass and pike from getting upriver and destroying native fish. The rapid exists because Lake Mead, sitting at just 43 percent of capacity, is so low that the inflow to it from the river has carved a new entry where the river plunges over a bedrock ledge.

If Lake Mead ever began to fill again, it would inundate Pearce Ferry Rapid, allowing the non-native fish to migrate upstream and prey on native Colorado River fish. “They would just eat and eat,” said Rice, with American Rivers. “All the recovery of endangered fish could be for naught.”

Playing the Waiting Game

During a period of great uncertainty about what the next water year will bring, Colorado River water users will need to think creatively while using all their tools, including storage.

“Glen Canyon Dam exists because you need all that potential storage,” said Schmidt, with Utah State University. “In some freak years you are going to get really big runoff, and nobody wants to see that go through the system.”

Meanwhile, the lake’s future role in

the Colorado River Basin is a key topic as Reclamation reviews

the performance of the 2007 Guidelines, with results expected at

the end of this year at the annual meeting of Colorado River

water users.

Meanwhile, the lake’s future role in

the Colorado River Basin is a key topic as Reclamation reviews

the performance of the 2007 Guidelines, with results expected at

the end of this year at the annual meeting of Colorado River

water users.

Pellegrino with Southern Nevada Water Authority said it would be nice to get past the controversy about Lake Powell’s releases and instead find ways to store more water in it. “We have had a lot of consternation … more because of the balancing releases than the actual behavior of any water user or basin,” she said. “Going back to something that’s more constant or more fixed would remove an element of consternation between the Basins.”

What’s likely to happen is an approach that builds upon the years of collaboration and cooperation established between everyone working on Colorado River water management, said Tina Shields, water manager with the Imperial Irrigation District, the largest user of Colorado River water.

“We know how the river works – its incrementalism,” she said. “Nobody wants to make wholesale changes because it’s too big of a deal and what if it went south? We are not quick to change these relationships and negotiations. They took a lot of time.”

Chris Harris, executive director of the Colorado River Board of California, said Reclamation’s findings will be key in considering the continued conjunctive management of Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

“There are 40 million people who rely on water from this river and over the last 20 years, we would not have been able to supply that water reliably without these storage reservoirs.”

~Marlon Duke, Bureau of Reclamation

“Certainly, the [2007] Guidelines have shown that managing the reservoirs together has kept Lake Powell from crashing and has kept Lake Mead from a shortage condition,” he said. “I believe that there will be significant interest in evaluating opportunities, including with Mexico, for even more effective management of the reservoir system.”

That process will most likely look at different elevations and trigger points for excess releases from Lake Powell in a manner that’s acceptable to the Upper and Lower Basins.

“The question is, how do you get movement either way without someone saying, ‘That doesn’t work for me,’” Shields said. “Sometimes the status quo is easier to continue than the fear associated with changing those trigger points.”

As with virtually all Colorado River issues, the ramifications of actions can run far and wide. “This sounds like an esoteric argument about something hundreds of miles away, but the reality of it is what happens at Lake Powell affects the amount of water available to the Lower Basin states, Southern California and, indirectly, Northern California,” said Beard, the former Reclamation commissioner.

California’s extensive water plumbing network relies on a careful balance of imports to Southern California from Northern California and the Colorado River.

Even with Reclamation’s review of the guidelines expected to be issued at the end of the year, Schmidt with Utah State University said he believes stakeholders will let multiple years pass before committing to any radical operational changes.

“Every year that we wait buys a little more information about climate change and decreasing runoff and whether we go into a wet cycle,” he said. “There’s a lot of things that could happen and people will hope that nature provides a favorable condition so there can be a tiny bit more wiggle room and we don’t go into dire crisis.”

Haas echoed the comments of many stakeholders in noting that all options for Powell’s operation should be considered. “It’s not heretical to be thinking outside the norm on things,” she said. “It spurs a more robust discussion and we should not shy away from that.”

Reclamation’s Duke harkens back to Powell’s ability to consistently meet and sometimes exceed its release obligations during severe conditions.

“That is a testament to the people who came before and had to make those tough calls,” he said. “They built that reservoir and it’s done what we needed. Looking into the future, everything’s on the table, but we also need to remember there are 40 million people who rely on water from this river and over the last 20 years, we would not have been able to supply that water reliably without these storage reservoirs.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @GaryPitzer

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn.

Further Reading

- Western Water: Can a Grand Vision Solve the Colorado River’s Challenges? Or Will Incremental Change Offer Best Hope for Success? Dec. 13, 2019

- Western Water: Could “Black Swan” Events Spawned by Climate Change Wreak Havoc in the Colorado River Basin? Sept. 12, 2019

- Western Water: With Drought Plan in Place, Colorado River Stakeholders Face Even Tougher Talks Ahead On The River’s Future, May 9, 2019

- Western Water: As Shortages Loom in the Colorado River Basin, Indian Tribes Seek to Secure Their Water Rights, Nov. 2, 2018

- Western Water: Despite Risk of Unprecedented Shortage on the Colorado River, Reclamation Commissioner Sees Room for Optimism, Sept. 21, 2018

- Western Water: New Leader Takes Over as the Upper Colorado River Commission Grapples With Less Water and a Drier Climate, Aug. 10, 2018

- Aquapedia: Colorado River