Hydroelectric Power

Hydroelectric power is a relatively

pollution-free source of electricity generated at a comparatively

low cost. Its ability to generate electricity, however, can drop

significantly during a drought.

Hydroelectric power is a relatively

pollution-free source of electricity generated at a comparatively

low cost. Its ability to generate electricity, however, can drop

significantly during a drought.

In 2022, hydropower accounted for more than 28% of all renewable electricity generation in the nation, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

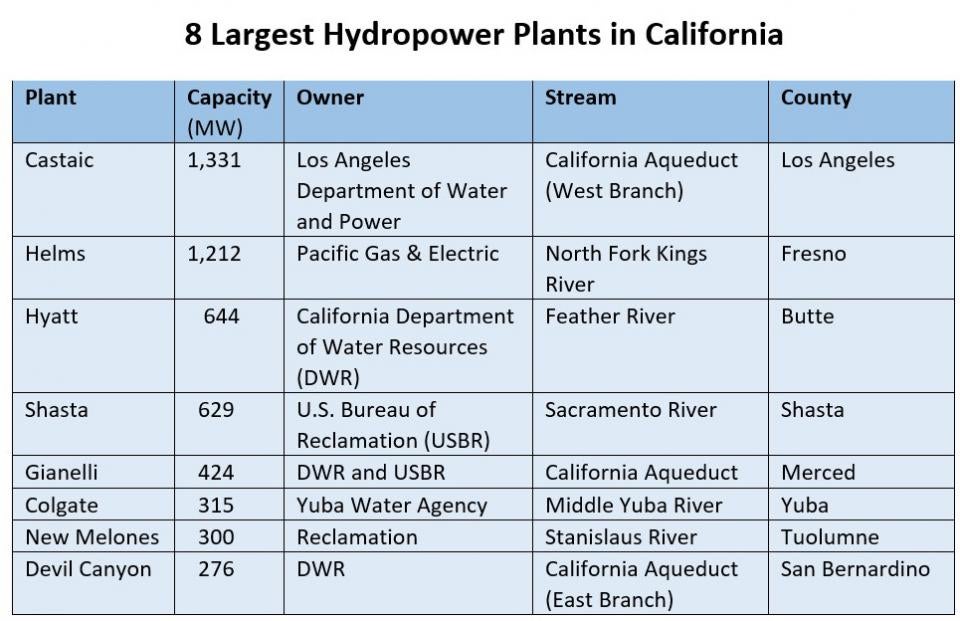

California has 343 hydroelectric plants of various generation capacities owned by a mix of private and public energy utilities, government agencies and private companies. Some of the dams were built in the early 1900s. California also pulls in out-of-state hydroelectric power, mostly from the Hoover Dam in Nevada.

Most of California’s hydroelectric plants are at reservoirs that also provide water supply, flood control and recreation. All but the federal powerhouses are licensed and regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

Variable Production

The amount of hydropower production varies from year to year, month to month and day to day, depending on several factors – particularly the amount of snow and rainfall in upper watersheds.

In an average water year, about 4.5 million megawatt hours of energy are produced. (A megawatt hour is roughly equivalent to the amount of electricity used by about 330 homes for one hour.)

In 2022, hydropower’s share of total electricity generation in California was about 10 percent. The powerhouses generated a combined 17,000 megawatt hours of electricity that year, enough to power about 5.6 million homes for one hour.

In 2015, drought conditions caused hydroelectric power generation to account for only 7 percent of the state’s total supply of electricity.

How It Works

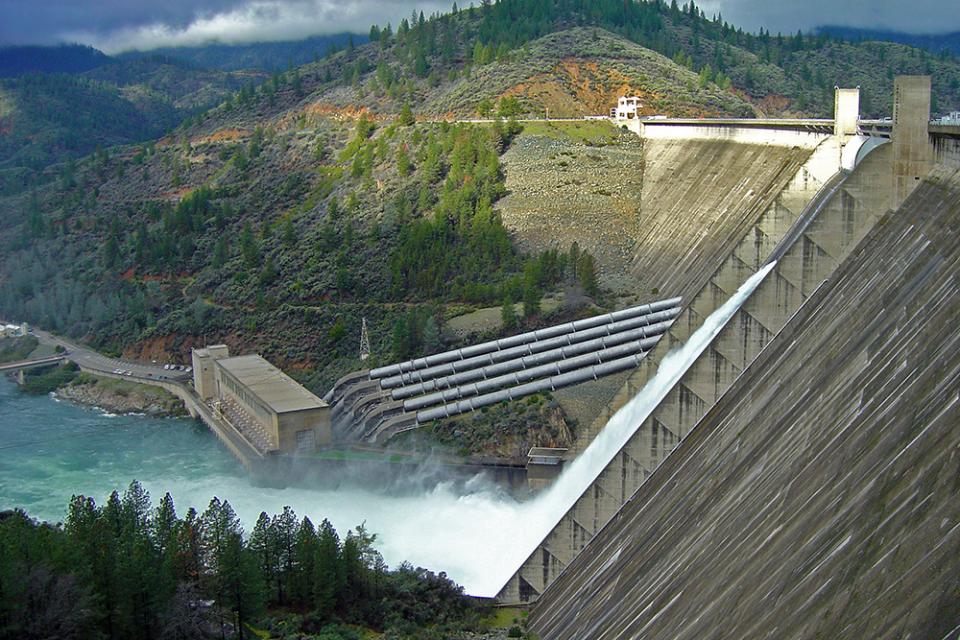

A hydroelectric power plant generates electricity by using the gravitational energy of water falling from a higher to lower elevation. The higher the fall and the greater the flow, the more the electricity that can be generated.

Video: See how the Castaic hydroelectric plant works.

The water typically enters the plant through a pipe, known as a penstock, and then spins the blades in a turbine, which, in turn, spins a generator that produces electricity. The electricity is then fed into an electrical grid to power homes, businesses and industries.

Environmental Impact

Hydropower, a relatively pollution-free source of electricity, has helped lessen dependence on oil, gas and coal. Hydropower also has spurred agricultural and industrial productivity by pumping millions of gallons of fresh water to the semi-arid Central Valley and Southern California.

But hydroelectric power can have a significant impact on the health of ecosystems. Dams and reservoirs can change stream flows, water temperature, turbidity (amount of sediment in the water) and oxygen content. The changes can disrupt the lifecycles of fish and other aquatic life.

However, the amount and timing of dam releases can be arranged to mimic the natural water flows of the river.

Some obsolete hydropower

dams have been

removed to restore river ecosystems and native fish

populations. Starting in 2011, the National Park Service

removed two obsolete dams from Washington’s Elwha River in

Olympic National Park, allowing federally threatened salmon, bull

trout and steelhead to approach the river’s headwaters for the

first time in nearly a century.

Some obsolete hydropower

dams have been

removed to restore river ecosystems and native fish

populations. Starting in 2011, the National Park Service

removed two obsolete dams from Washington’s Elwha River in

Olympic National Park, allowing federally threatened salmon, bull

trout and steelhead to approach the river’s headwaters for the

first time in nearly a century.

The Klamath River in Oregon and California is also being given a chance to return to a more natural state. In the nation’s largest dam removal project ever undertaken, construction crews in 2023 tore down the first of four essentially defunct power dams choking a 64-mile stretch, with the remaining three slated to come out by the end of 2024.

Climate Change

California’s ability to meet hydropower demand in the face of rising temperatures could be problematic. The anticipated reduction in runoff resulting from climate change means that less water will be available for hydroelectric generation.

In August 2021, a major California hydropower plant was shut down due to low water levels for the first time since it opened in 1968. The state-run Edward Hyatt Powerplant at Lake Oroville. The plant resumed operations five months later.

Scientists say California’s historic 2021 drought could be part of a long-term period of dryness. Further below-average water years could have major consequences on hydroelectric power generation at large reservoirs such as Lake Oroville as operators struggle to balance releases for urban uses, agriculture and the environment.