Klamath River Basin

The Klamath River Basin is one of the West’s most important and contentious watersheds.

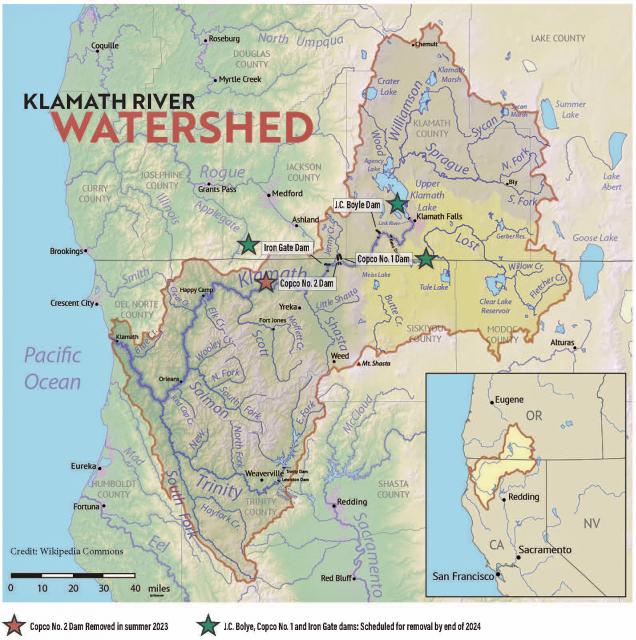

The watershed is known for its unusual geography straddling California and Oregon. Unlike many western rivers, the Klamath does not originate in snowcapped mountains but rather on a volcanic plateau.

A broad patchwork of spring-fed streams and rivers in south-central Oregon drains into Upper Klamath Lake and down into Lake Ewauna in the city of Klamath Falls. The outflow from Ewauna marks the beginning of the 263-mile Klamath River.

The Klamath courses south through the steep Cascade Range and west along the rugged Siskiyou Mountains to a redwood-lined estuary on the Pacific Ocean just south of Crescent City, draining a watershed of 10 million acres.

A bounty of resources – water, salmon, timber and minerals – and a wide range of users turned the remote region into a hotspot for economic development and multiparty water disputes (See Klamath River timeline).

Though the basin has only 115,000 residents, there is seldom enough water to go around. Droughts are common. The water scarcity inflames tensions between agricultural, environmental and tribal interests, namely the basin’s four major tribes: the Klamath Tribes, the Karuk, Hoopa Valley and Yurok. Klamath water-use conflicts routinely spill into courtrooms, state legislatures and Congress.

In 2023, a historic removal of four powers dams on the river began, signaling hope for restoration of the river and its fish and easing tensions between competing water interests. In February 2024, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland announced a “historic” agreement between tribes and farmers in the basin over chronic water shortages. The deal called for a wide range of river and creek restoration work and modernization of agricultural water supply infrastructure.

Water Development

Farmers and ranchers have drawn irrigation water from basin rivers and lakes since the late 1900s. Vast wetlands around Upper Klamath Lake and upstream were drained to grow crops. Some wetlands have been restored, primarily for migratory birds.

In 1905, the federal government authorized construction of the Klamath Project, a network of irrigation canals, storage reservoirs and hydroelectric dams to grow an agricultural economy in the mostly dry Upper Basin. The Project managed by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation irrigates about 240,000 acres and supplies the Lower Klamath Lake and Tule Lake national wildlife refuges managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Water Management

Since 1992, federal mandates to restore populations of fish protected by the Endangered Species Act have led in some dry years to drastic cuts in water deliveries to Klamath Project irrigators.

Water in Upper Klamath Lake must be kept above certain levels for the endangered shortnose and Lost River suckers. Lake levels and Klamath River flows below Iron Gate Dam also must be regulated for the benefit of threatened coho salmon (See Klamath Basin Chinook and Coho Salmon).

Conflict

In 2001, Reclamation all but cut off irrigation water to hundreds of basin farmers and ranchers, citing a severe drought and legal obligations to protect imperiled fish. In response, thousands of farmers, ranchers and residents flocked to downtown Klamath Falls to form a “bucket brigade” protest, emptying buckets of water into the closed irrigation canal. The demonstrations stretched into the summer, with protestors forcing open the irrigation headgates on multiple occasions. Reclamation later released some water to help farmers.

In September 2002, a catastrophic

disease outbreak in the lower Klamath River killed tens of

thousands of ocean-going salmon. The Pacific Coast Federation of

Fishermen’s Associations sued Reclamation, alleging the Klamath

Project’s irrigation deliveries had violated the Endangered

Species Act. The fishing industry eventually prevailed, and

a federal court ordered an increase to minimum flows in the lower

Klamath.

In September 2002, a catastrophic

disease outbreak in the lower Klamath River killed tens of

thousands of ocean-going salmon. The Pacific Coast Federation of

Fishermen’s Associations sued Reclamation, alleging the Klamath

Project’s irrigation deliveries had violated the Endangered

Species Act. The fishing industry eventually prevailed, and

a federal court ordered an increase to minimum flows in the lower

Klamath.

Compromise

The massive salmon kill and dramatic water shut-off set in motion a sweeping compromise between the basin’s many competing water interests: the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement and the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement. The 2010 agreements included:

- Removal of four hydroelectric dams

- $92.5 million over 10 years to pay farmers to use less water, increase reservoir storage and help pay for water conservation and groundwater management projects.

- $47 million over 10 years to buy or lease water rights to increase flows for salmon recovery.

Dam Removals

Congress never funded the two agreements, allowing the key provisions to expire. The restoration accord dissolved in 2016. The hydroelectric pact, however, was revived in an amended version that did not require federal legislation.

The new deal led to the nation’s largest dam removal project ever undertaken.

California and Oregon formed a

nonprofit organization called the Klamath River Renewal

Corporation to take control of the four essentially obsolete

power dams – J.C. Boyle, Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2 and Iron Gate –

and oversee a $450 million dam demolition and river restoration

project.

California and Oregon formed a

nonprofit organization called the Klamath River Renewal

Corporation to take control of the four essentially obsolete

power dams – J.C. Boyle, Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2 and Iron Gate –

and oversee a $450 million dam demolition and river restoration

project.

Taking out the dams will open more than 420 miles of river and spawning streams that had been blocked for more than a century, including cold water pools salmon and trout need to survive the warming climate.

Demolition crews took out the smallest dam in 2023 and all four dams were taken down by the end of 2024.

The images of yellow heavy machinery tearing into the dam’s spillway gates prompted a cathartic release for many who have been fighting for decades to open this stretch of the Klamath.

“I’m still in a little bit of shock,” said Toz Soto, the Karuk fisheries program manager. “This is actually happening…It’s kind of like the dog that finally caught the car, except we’re chasing dam removal.”

Updated June 2025