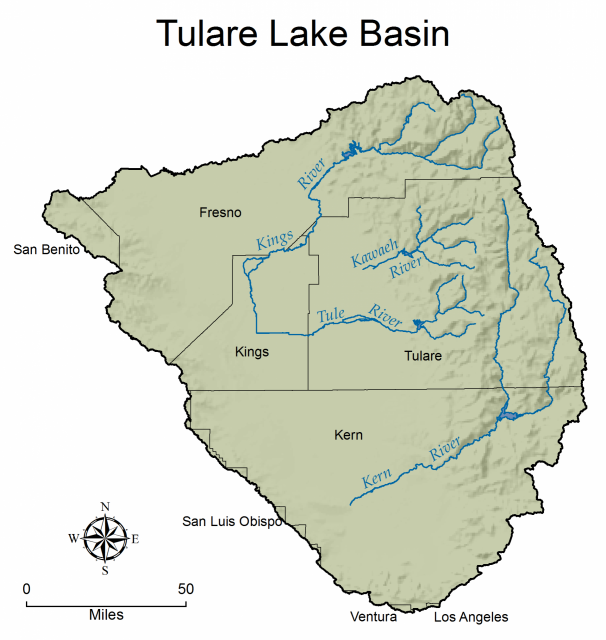

Tulare Lake Basin

Until the early 1900s, Central

California’s Tulare Lake appeared every winter as the

southernmost rivers flowing out of the Sierra Nevada filled the

dry lakebed with rainfall and melted snow.

Until the early 1900s, Central

California’s Tulare Lake appeared every winter as the

southernmost rivers flowing out of the Sierra Nevada filled the

dry lakebed with rainfall and melted snow.

In the spring, the shallow lake near Visalia could cover as much as 790 square miles or four times the surface area of Lake Tahoe. However, by the end of the hot San Joaquin Valley summer, the giant lake – once the largest freshwater body west of the Mississippi River – could disappear primarily due to evaporation.

Tulare Lake and its tule marsh complex that once dominated the Central California landscape are no longer featured on maps. The dormant lake reappears only during years of extreme precipitation in the central and southern Sierra, when dams on rivers that once fed the lake swell above their flood-control caps. The lake partly refilled in 1969, 1983, 1997, and again in 2023 when more than a dozen atmospheric rivers hit California.

In 2023, the revived lake caused widespread flooding of communities and farmland. The flooding was precipitated by heavy rainfall and meltwater from the largest snowpack ever recorded in the southern Sierra. The flooding caused billions of dollars in farming losses in parts of Fresno, Kern, Kings and Tulare counties.

History

Tulare Lake was originally home to the Yokuts, a group of Native American tribes that spoke similar languages and lived near the Kings, Kaweah, Tule and Kern rivers that fed the lake. For thousands of years, the tribes thrived in the basin’s diverse habitats, from wetlands and vernal pools to oak woodlands and riparian forests. The Yokuts enjoyed abundant wildlife and native fish, including pikeminnow, hitch and chinook salmon.

The Tulare Lake Basin dramatically changed after the Gold Rush as miners left the mountains for the valley. The new settlers drove out the Indigenous communities, diverted the rivers and drained the marshes for farming. They built canals, levees and eventually dams, notably Pine Flat on the Kings River, Terminus on the Kaweah and Success on the Tule—robbing the lake of its water sources.

By the early 20th century, the basin had been transformed into one of the best cotton-growing regions in the nation. Today, the former lakebed hosts a wider variety of crops such as tomatoes, wheat and almonds but is best known for being one of the top-producing dairy regions in the nation.

Farm Drainage

The Tulare Lake Basin doesn’t have an outlet, so controlling salinity levels is critical to protecting the health of the soil and groundwater.

Fertilizers and livestock waste in

farm drainage and irrigation water imported from the

Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta contain salts that can render

farmland less fertile and groundwater undrinkable. To lessen the

damage, the runoff from nearly 50,000 acres of farmland is stored

in a network of four evaporation catchments stretching across

5,250 acres, known as the North, South, Hacienda and MEB basins.

Fertilizers and livestock waste in

farm drainage and irrigation water imported from the

Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta contain salts that can render

farmland less fertile and groundwater undrinkable. To lessen the

damage, the runoff from nearly 50,000 acres of farmland is stored

in a network of four evaporation catchments stretching across

5,250 acres, known as the North, South, Hacienda and MEB basins.

While the containment has improved crop production, the high concentrations of salt and other wastes pose risks to waterfowl and shorebirds.

The state’s Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board monitors Tulare Lake Drainage District as part of its job policing agricultural runoff. The district operates a 307-acre habitat restoration site to limit harm to waterbirds, primarily American avocets and black-necked stilts. It also manages a 305-acre area designed as a winter wetland for dabbling and diving ducks. The site is designed to facilitate flooding and draining at different rates to create a mosaic of habitats for these birds.

Long-term solutions for the Tulare runoff don’t come easily. Some local drainage managers believe the best solution is to build a drain to the Pacific Ocean, but state regulators say the economic and environmental costs would be too high.

Land Subsidence

For decades, farms and communities in the more arid parts of California have overpumped groundwater, depleting it faster than it is replenished. The California Department of Water Resources (DWR) has designated several groundwater subbasins beneath the lakebed as “critically overdrafted,” including Tulare Lake, Tule and Kaweah subbasins.

Overpumping has caused water tables to drop, land to sink near roads and canals and decreased water quality basinwide. (See Land Subsidence.)

The Tulare Lake Basin is one of the fastest-sinking areas in the nation because of chronic overpumping by growers. Some places are sinking a foot a year, causing roads and canals to buckle. Subsidence caused the Friant-Kern Canal to lose 60 percent of its water-carrying capacity and a 33-mile section of the channel had to be rebuilt.

In 2022, DWR determined that groundwater agencies in Kings County did not adequately address these problems in their Tulare Lake Groundwater Sustainability Plan. The local agencies revised the plan, but DWR rejected it again in 2023 and deemed plans for the Tule and Kaweah subbasins inadequate.

At a hearing in 2024, the State Water Resources Control Board voted unanimously to put the Tulare Lake subbasin on “probation” for failing to curb growers’ overpumping. It was the first time California officials had used their authority to intervene in a community to rein in groundwater depletion, as required under the state’s decade-old Sustainable Groundwater Management Act.

The April 16, 2024 order could eventually lead to the state taking control of groundwater pumping in the severely depleted basin. Under probation, agricultural landowners in the area will be required to start reporting to the state how much water they pump from wells and paying fees based on how much they use.

Updated April 2024