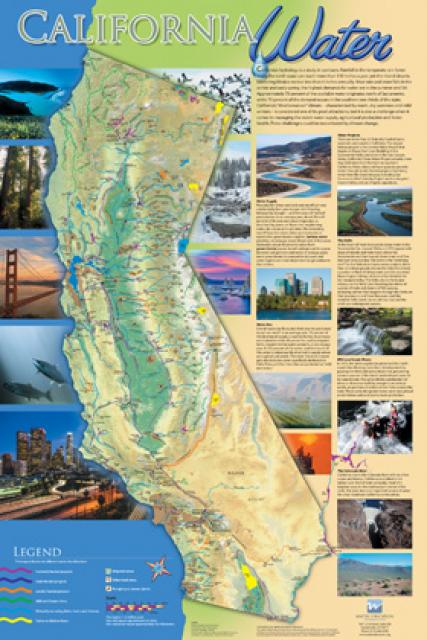

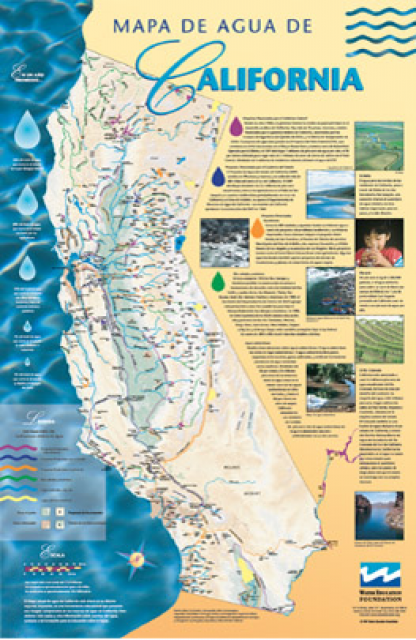

Owens Valley and Los Angeles Aqueduct

The Owens Valley in eastern

California helped transform distant Los Angeles into today’s

sprawling megalopolis.

The Owens Valley in eastern

California helped transform distant Los Angeles into today’s

sprawling megalopolis.

More than 100 years ago, Los Angeles recognized the need to augment local water supplies and decided to tap faraway sources.

In 1905, the city filed for water rights on the Owens River in the eastern Sierra Nevada, 250 miles away. Municipal crews began work on a 233-mile aqueduct capable of delivering four times more water than the city then required. The Los Angeles Aqueduct was completed in 1913, and with this firm water supply, the city grew. By 1920, Los Angeles was as populous as San Francisco.

To protect its rights, Los Angeles began buying land and associated water rights in the Owens Valley and converting cropland to a less water-intensive use: cattle grazing. Irrigated acreage in the valley dropped from about 75,000 acres in 1920 to 23,625 acres in 1940.

Early on, in 1924, area ranchers and businessmen feared for the valley’s agricultural future and waged a “water war,” dynamiting the aqueduct 17 times in a futile attempt to stop the water from flowing south.

With Los Angeles as landlord, the

Owens Valley became a recreation area with leased rather

than owner-occupied farms.

With Los Angeles as landlord, the

Owens Valley became a recreation area with leased rather

than owner-occupied farms.

Today, Los Angeles controls nearly all the land on the valley floor. Until recent court decisions reduced the amount of exported water, valley water provided up to 75 percent of the city’s annual supply. After years of legal battles, Inyo County and Los Angeles agreed in 1991 to jointly manage the valley’s water and regulate the amount of exported water based on environmental effects.

The water exports also created an air pollution hazard in the Owens Valley. Diverting the Owens River and streams feeding the 100-square-mile Owens Lake left it mostly dry. Aerosols of fine mineral dust from the lake bed raised health concerns among the region’s residents, particularly those with respiratory problems. Since the 1990s, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power has spent more than $2.5 billion on projects that have reduced dust emissions by nearly 100%, according to the utility